The HDL Paradox: Rethinking the 'Good' Cholesterol

Feb 17

/

Drs. Bryan & Julie Walsh

Introduction

A recent study published in the British Journal of Ophthalmology gained some media attention because it suggested a potential link between elevated HDL cholesterol levels and increased glaucoma risk. While this finding may surprise those who still think of HDL as simply the "good cholesterol," it adds to a growing body of evidence that challenges our traditional understanding of HDL's role in health and disease, much of which we've been following, and teaching about, for years. Thus, we felt it was time to tackle these complex and sometimes paradoxical relationships between HDL cholesterol levels and various health outcomes and move beyond the oversimplified "higher is better" paradigm that has dominated both medical practice and public understanding for decades.

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) has been hailed as the "good cholesterol," a label that has become deeply ingrained in both the medical world as well as in the public consciousness. This widely accepted belief stems from countless observational studies that consistently demonstrate an inverse relationship between HDL-C levels and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. However, on the other side of the lipoprotein coin, there is considerable mounting evidence that challenges this simplistic view and not surprisingly, reveals a far more complex and nuanced role for HDL in human health and disease.

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) has been hailed as the "good cholesterol," a label that has become deeply ingrained in both the medical world as well as in the public consciousness. This widely accepted belief stems from countless observational studies that consistently demonstrate an inverse relationship between HDL-C levels and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. However, on the other side of the lipoprotein coin, there is considerable mounting evidence that challenges this simplistic view and not surprisingly, reveals a far more complex and nuanced role for HDL in human health and disease.

In light of some of this research, the myopic view that "higher is better" when it comes to HDL-C levels needs to be strongly re-evaluated. Large-scale epidemiological studies and genetic analyses have uncovered a paradoxical relationship regarding HDL-C – that while moderate levels appear protective, high levels may be associated with increased mortality and morbidity. This finding should make all nutritional and functional medicine practitioners reconsider our understanding of HDL's role in health and disease, which suggests that the relationship between HDL-C and cardiovascular risk is not linear, but instead follows a U-shaped curve.

If it turns out that there is an upper end of HDL cholesterol that might indicate some degree of pathology, it could fundamentally change how we interpret and utilize HDL-C measurements in clinical practice. Instead of overly simplistic categorizations of "good" and "bad" cholesterol, we would have to have a more sophisticated understanding of lipid metabolism and its impact on human health.

Historical Perspective: HDL as a Cardiovascular Protector

The story of HDL as a cardiovascular protector began in the mid-20th century (1948) with the oft-cited Framingham Heart Study. This long-term, ongoing cardiovascular cohort study provided some of the first evidence for a possible inverse relationship between HDL-C levels and CVD risk. In 1977, Gordon et al. published a seminal paper based on Framingham data, demonstrating that HDL-C was a powerful inverse predictor of coronary heart disease risk [1].

The apparent cardioprotective effects of HDL were attributed to its role in reverse cholesterol transport (RCT), a process by which excess cholesterol is removed from peripheral tissues and transported to the liver for excretion. This mechanism was first proposed by Glomset in 1968, providing a plausible biological explanation for HDL's observed benefits [3].

As evidence accumulated over the years, the medical community embraced HDL-C as a key marker of cardiovascular health. By the 1980s and 1990s, national guidelines began incorporating HDL-C levels into risk assessment algorithms and treatment recommendations. For example, the National Cholesterol Education Program's Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines, published in 2001, identified low HDL-C as a major risk factor for coronary heart disease and set specific target levels for HDL-C in clinical practice [4].

This progression of studies and findings firmly placed HDL-C at the center of cardiovascular risk assessment and as a potential therapeutic target. However, as we shall see, research would eventually challenge this overly simplistic interpretation, revealing a far more complex relationship between HDL and cardiovascular health.

This initial finding was further corroborated by numerous subsequent epidemiological studies. For example, the Prospective Cardiovascular Münster (PROCAM) study, another landmark investigation, confirmed the strong inverse association between HDL-C levels and coronary artery disease risk [2]. These studies, among others, laid the foundation for the "HDL hypothesis," which posited that raising HDL-C levels would reduce cardiovascular risk.

The apparent cardioprotective effects of HDL were attributed to its role in reverse cholesterol transport (RCT), a process by which excess cholesterol is removed from peripheral tissues and transported to the liver for excretion. This mechanism was first proposed by Glomset in 1968, providing a plausible biological explanation for HDL's observed benefits [3].

As evidence accumulated over the years, the medical community embraced HDL-C as a key marker of cardiovascular health. By the 1980s and 1990s, national guidelines began incorporating HDL-C levels into risk assessment algorithms and treatment recommendations. For example, the National Cholesterol Education Program's Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines, published in 2001, identified low HDL-C as a major risk factor for coronary heart disease and set specific target levels for HDL-C in clinical practice [4].

This progression of studies and findings firmly placed HDL-C at the center of cardiovascular risk assessment and as a potential therapeutic target. However, as we shall see, research would eventually challenge this overly simplistic interpretation, revealing a far more complex relationship between HDL and cardiovascular health.

Don’t let misinformation compromise your practice—get the facts and make smarter, evidence-based decisions today!

Download your FREE copy of Overloaded: An Evidence-Based Guide to Rethinking Dietary Supplements.

Cut through the hype, avoid common clinical pitfalls, and gain the clarity to confidently recommend dietary supplements—backed by over 180 scientific references.

The U-Shaped Curve: When More Isn't Better

The traditional view of HDL-C as uniformly protective has been significantly challenged by recent large-scale epidemiological studies. These investigations have revealed a more complex, non-linear relationship between HDL-C levels and mortality risk, often described as a U-shaped or J-shaped curve. This pattern suggests that both very low and very high levels of HDL-C may be associated with increased risk, contradicting the long-held belief that higher HDL-C levels are always better.

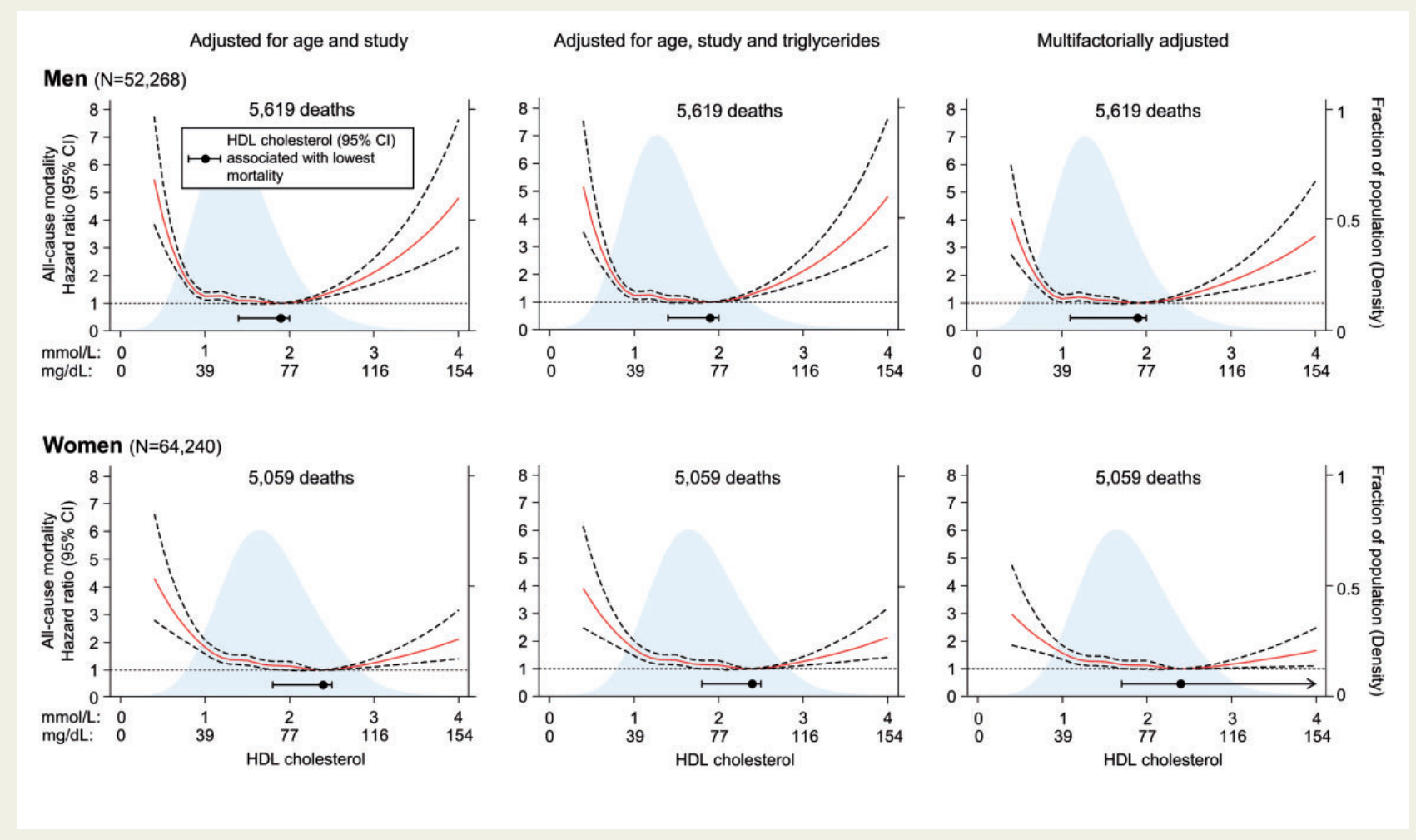

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence comes from a study by Madsen et al., published in the European Heart Journal in 2017 [5]. This investigation, which included over 116,000 individuals from the Copenhagen General Population Study and the Copenhagen City Heart Study, found that extremely high HDL-C levels were paradoxically associated with high all-cause mortality in both men and women. Specifically, men with HDL-C levels above 97 mg/dL (2.5-2.99 mmol/L) had a 36% higher risk of all-cause mortality compared to those with HDL-C levels of 58-76 mg/dL (1.5-1.99 mmol/L). For women, HDL-C levels above 135 mg/dL (3.5 mmol/L) were associated with a 68% higher risk compared to the reference range of 77-96 mg/dL (2.0-2.49 mmol/L) (Figure 1). Granted, these are significantly higher levels than what is on a standard blood chemistry lab, or that one might see in otherwise healthy individuals, but it serves as a starting point.

Figure 1 - Madsen CM, Varbo A, Nordestgaard BG. Extreme high high-density lipoprotein cholesterol is paradoxically associated with high mortality in men and women: two prospective cohort studies. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(32):2478-2486. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx163

Another large-scale study, the CANHEART study by Ko et al., published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology in 2016, examined over 630,000 individuals without pre-existing cardiovascular conditions [6]. This study also found a U-shaped relationship between HDL-C levels and both cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular mortality. Individuals with very low HDL-C levels (≤30 mg/dL) and very high levels (>90 mg/dL in women, >80 mg/dL in men) had higher mortality rates compared to those with intermediate levels. Note that while the upper end wasn’t stated here, the cutoffs are considerably lower than in the previous study by Madsen.

These findings have been further corroborated by other studies. A pooled analysis of nine cohort studies in Japan (EPOCH-JAPAN study) by Hirata et al., including over 43,000 individuals, demonstrated that extremely high HDL-C levels (≥90 mg/dL) were associated with increased cardiovascular mortality [7].

The consistency of these findings across different populations and study designs strongly suggests that the relationship between HDL-C and mortality risk appears to be non-linear. This U-shaped relationship challenges the overly simplistic "higher is better" paradigm and requires that we have a much more nuanced approach to interpreting HDL-C levels in clinical practice.

"The myopic view that 'higher is better' when it comes to HDL-C levels needs to be strongly re-evaluated. Large-scale epidemiological studies and genetic analyses have uncovered a paradoxical relationship regarding HDL-C - that while moderate levels appear protective, high levels may be associated with increased mortality and morbidity."

Potential Mechanisms of Harm

As you can imagine, after researchers began observing this U-shaped phenomenon, their next logical question was, “Why?” The unexpected association between very high HDL-C levels and increased mortality risk prompted researchers to investigate potential mechanisms that could explain this paradox. Several hypotheses have been proposed, most of them focusing on the possibility that HDL particles may become dysfunctional or even pro-inflammatory under certain conditions.

This evidence of potential harm, either caused by or associated with, elevated HDL-C levels underscores the complexity of lipid metabolism and the limitations of using HDL-C concentration alone as a marker of cardiovascular health. It highlights the need for a more comprehensive approach that considers not just the quantity of HDL-C, but perhaps its quality and functionality as well.

- HDL Particle Dysfunction: At very high concentrations, HDL particles may undergo structural and functional changes that impair their protective properties. Huang et al. demonstrated that HDL from patients with very high HDL-C levels had impaired cholesterol efflux capacity, a key measure of HDL functionality [8]. This suggests that beyond a certain threshold, additional HDL-C may not contribute to improved reverse cholesterol transport. Cholesterol efflux and reverse cholesterol transport refer to the ability of HDL to remove lipids from tissues which, ironically, might be impaired when HDL levels increase.

- Pro-inflammatory Conversion: Under certain conditions, HDL particles can become pro-inflammatory rather than anti-inflammatory. Ansell et al. showed that HDL from patients with coronary artery disease had pro-inflammatory properties, despite normal or high HDL-C levels [9]. This "dysfunctional HDL" may contribute to atherosclerosis progression rather than protection.

- Altered HDL Composition: Extremely high HDL-C levels may reflect alterations in HDL particle composition. Kontush and Chapman proposed that changes in the lipid and protein content of HDL particles at high concentrations could affect their functionality [10]. For example, cholesterol-overloaded HDL particles might be less effective at performing their atheroprotective functions of reverse cholesterol transport due to already being overly filled with lipids.

- Genetic Factors: Genetic variants associated with very high HDL-C levels have been linked to increased cardiovascular risk. Zanoni et al. identified a rare variant in the scavenger receptor BI gene (SCARB1) that was associated with elevated HDL-C levels but also with an increased risk of coronary heart disease [11]. While this genetic variant is rare, it suggests that some genetic mechanisms that raise HDL-C may simultaneously increase cardiovascular risk through other pathways.

- Impaired HDL Catabolism: If there is ever too much of something in the body, it might not be due to increased production, but rather the converse, decreased breakdown. Extremely high HDL-C levels could therefore result from impaired catabolism of HDL particles. It has been suggested that if HDL particles remain in circulation for too long, they may accumulate oxidative modifications that compromise their protective functions [12].

- Reverse Causality: Finally, we would be remiss if we didn’t consider the possibility that very high HDL-C levels are a marker of underlying metabolic disturbances rather than a direct cause of harm. For instance, certain chronic diseases or metabolic states might lead to both elevated HDL-C and increased mortality risk.

These potential mechanisms are not mutually exclusive, and the observed harm associated with very high HDL-C levels likely results from a combination of factors. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for developing more effective strategies for cardiovascular risk assessment and management than merely evaluating HDL levels as the “good” cholesterol.

This evidence of potential harm, either caused by or associated with, elevated HDL-C levels underscores the complexity of lipid metabolism and the limitations of using HDL-C concentration alone as a marker of cardiovascular health. It highlights the need for a more comprehensive approach that considers not just the quantity of HDL-C, but perhaps its quality and functionality as well.

HDL's Complex Role in Health

HDL and Infection Risk

While HDL has traditionally been studied in the context of cardiovascular disease, recent research has unveiled its significant role in the immune response and infection risk. This multifaceted function of HDL adds an entirely new layer of complexity to our understanding of its impact on overall health.

It turns out that HDL particles play a crucial role in the innate immune system as well, particularly in the response to bacterial infections. One of the key mechanisms involves the binding and neutralization of lipopolysaccharides (LPS), also known as endotoxins, which are components of gram-negative bacterial cell walls. LPS can trigger a potent inflammatory response that, if unchecked, can lead to sepsis, and even at low levels, lead to some degree of chronic inflammation.

Here are some ways HDL cholesterol interacts with and is involved in the innate immune system:

- LPS Binding and Neutralization: HDL particles, particularly through the action of apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I), can bind and neutralize LPS, thereby mitigating its pro-inflammatory effects. Levels et al. demonstrated that reconstituted HDL could reduce LPS-induced inflammation in human volunteers, suggesting a protective role against sepsis [13]. Based on this mechanism, it would stand to reason that the presence of HDL might be a reason for higher levels of circulating HDL as a protective mechanism by the body.

- Modulation of Immune Cell Function: HDL interacts with various immune cells, influencing their function. For instance, HDL can modulate the activity of macrophages involved in the innate immune response. Murphy et al. showed that HDL could inhibit macrophage activation and cytokine production in response to LPS stimulation [14].

- Antiviral Properties: Beyond bacterial infections, HDL has also been implicated in antiviral defense as well. Singh et al. reported that HDL can inhibit HIV-1 infectivity by modulating lipid raft composition in target cells [15].

However, the relationship between HDL levels and infection risk is not straightforward. While moderate levels of HDL appear protective, extremely high levels seem to paradoxically increase infection risk:

- U-shaped Relationship with Infection Risk: Madsen et al., in their study of over 100,000 individuals from the Copenhagen General Population Study, found a U-shaped association between HDL-C levels and risk of infectious disease [16]. Both very low (<31 mg/dL for men, <39 mg/dL for women) and very high (>100 mg/dL for men, >120 mg/dL for women) HDL-C levels were associated with increased risk of infectious disease compared to intermediate levels.

- Potential Mechanisms of Increased Risk: The mechanisms underlying increased infection risk at very high HDL-C levels are not fully understood. Hypotheses include potential interference with normal immune function or alterations in HDL particle composition that may impair its immunomodulatory properties.

- COVID-19 and HDL: Recent studies have also explored the role of HDL in COVID-19 outcomes. Wei et al. reported that low HDL-C levels were associated with higher risk of severe COVID-19 [17]. However, the impact of very high HDL-C levels in this context remains to be fully elucidated.

These findings highlight the complex role of HDL in infection and immunity. They suggest that maintaining HDL-C levels within an optimal range may be important not just for cardiovascular health, but also for supporting proper immune function and reducing infection risk.

HDL in Cancer and Other Diseases

The role of HDL extends beyond cardiovascular disease and infection, with evidence also suggesting complex associations with cancer and various other health conditions. These relationships further underscore the multifaceted nature of HDL's impact on human health.

- HDL and Cancer Risk: The relationship between HDL-C levels and cancer risk is complex and appears to vary by cancer type:

- Overall Cancer Risk: Several large-scale studies have observed a U-shaped relationship between HDL-C levels and cancer risk. For instance, the CANHEART study by Ko et al. found that both very low and very high HDL-C levels were associated with increased cancer mortality [6].

- Site-Specific Cancers: The association between HDL-C and cancer risk varies by cancer type. A study by Jafri et al. found that high HDL-C levels were associated with increased risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women [18]. Conversely, low HDL-C levels have been associated with increased risk of lung cancer and colorectal cancer [19].

- Potential Mechanisms: The mechanisms underlying these associations are not fully understood. HDL particles may influence cancer risk through their effects on inflammation, cell signaling, and cholesterol metabolism in cancer cells. Additionally, some genetic variants that raise HDL-C levels may independently affect cancer risk.

- HDL and Neurodegenerative Diseases:

- Alzheimer's Disease: As one can imagine by now, the relationship between HDL-C and Alzheimer's disease (AD) is also complex. While some studies suggest that high HDL-C levels may be protective against AD, others have found no association or even a potential increased risk at very high levels. Button et al. reviewed the role of HDL in AD, highlighting its potential neuroprotective effects but also noting the complexity of the relationship [20].

- Parkinson's Disease: Some studies have suggested a potential protective effect of higher HDL-C levels against Parkinson's disease, although the evidence is not conclusive [21].

- HDL and Autoimmune Diseases:

- Rheumatoid Arthritis: Patients with rheumatoid arthritis often have altered lipid profiles, including lower HDL-C levels. However, the functional properties of HDL may be more important than its concentration in this context [22].

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE): SLE patients often have dyslipidemia, including low HDL-C levels. Moreover, the anti-inflammatory functions of HDL may be impaired in SLE, contributing to increased cardiovascular risk in these patients [23].

- HDL and Chronic Kidney Disease:

- Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD): CKD is associated with dyslipidemia, including low HDL-C levels. However, the relationship between HDL-C and outcomes in CKD patients is complex. Some studies have found a U-shaped relationship between HDL-C levels and mortality in CKD patients, with both very low and very high levels associated with increased risk [24].

- HDL and Liver Disease:

- Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD): Low HDL-C levels are common in NAFLD patients and are associated with disease severity. However, the causal relationship is unclear, and HDL dysfunction may play a more important role than HDL-C levels per se [25].

These diverse associations highlight the far-reaching impact of HDL on human health beyond its traditional role in cardiovascular disease. They underscore the need for a more nuanced understanding of HDL's functions and the potential limitations of using HDL-C levels alone as a marker of health status.

The complex and sometimes paradoxical relationships between HDL-C levels and various health outcomes emphasize the importance of considering HDL function and quality, rather than just quantity, in assessing its impact on health. This perspective challenges the simplistic view of HDL as uniformly beneficial and calls for a more sophisticated approach to lipid management in clinical practice.

The Limitations of HDL-C as a Biomarker

The accumulating evidence of HDL's complex and sometimes paradoxical relationships with various health outcomes underscores the limitations of using HDL cholesterol (HDL-C) concentration alone as a biomarker of cardiovascular health or overall well-being. While HDL-C levels have been a cornerstone of lipid assessment for decades, several key limitations have become apparent:

- Lack of Causality: Despite the strong inverse association between HDL-C levels and cardiovascular risk observed in epidemiological studies, genetic and interventional studies have failed to demonstrate a causal relationship. Mendelian randomization studies, for example, which use genetic variants as proxies for lifelong differences in HDL-C levels, have not shown that genetically raised HDL-C levels reduce cardiovascular risk [26]. This suggests that HDL-C may be a marker of cardiovascular health rather than a direct causal factor.

- Failure of HDL-C Raising Therapies: Clinical trials aimed at reducing cardiovascular risk by pharmacologically raising HDL-C levels have been largely unsuccessful. The failure of cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitors to reduce cardiovascular events despite significantly increasing HDL-C levels is a prime example [27]. These results challenge the notion that simply increasing HDL-C concentration is beneficial.

- U-shaped Relationship with Outcomes: As discussed earlier, very high HDL-C levels have been associated with increased mortality risk, contradicting the "higher is better" paradigm. This U-shaped relationship is not captured by traditional risk assessment tools that treat HDL-C as a linear variable [5,6].

- Heterogeneity of HDL Particles: HDL-C measurement provides information about the cholesterol content of HDL particles but does not reflect the heterogeneity (diversity or variety) of HDL subclasses or their functional properties. HDL particles vary in size, density, and composition, factors that can significantly influence their biological activities [28].

- Functionality Over Quantity: Emerging evidence suggests that the functional properties of HDL, such as its cholesterol efflux capacity, may be more important than its cholesterol content in determining cardiovascular risk. Rohatgi et al. demonstrated that cholesterol efflux capacity was inversely associated with cardiovascular events, independent of HDL-C levels [29].

- Context-Dependent Effects: The impact of HDL-C levels on health outcomes can vary depending on the presence of other risk factors or disease states. For example, the relationship between HDL-C and cardiovascular risk may differ in patients with chronic kidney disease or inflammatory conditions [30].

- Genetic and Environmental Influences: HDL-C levels are influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. While some genetic variants associated with high HDL-C are protective, others may increase cardiovascular risk. This genetic heterogeneity is not captured by HDL-C measurement alone [11].

- Dynamic Nature of HDL: HDL particles are dynamic entities that undergo constant remodeling in the circulation. Static measurement of HDL-C does not capture this dynamic nature or the rate of HDL particle turnover, which may be important determinants of HDL function [31].

- Lack of Information on HDL Subclasses: Different HDL subclasses (e.g., HDL2, HDL3) may have distinct biological effects. HDL-C measurement does not provide information about the distribution of these subclasses, which could be important for risk assessment [32].

- Interference from Other Conditions: Certain disease states or medications can alter HDL-C levels without necessarily changing cardiovascular risk. For example, some individuals with genetic mutations causing very high HDL-C levels may paradoxically have increased cardiovascular risk [33].

These limitations highlight the need for a more comprehensive and nuanced approach to assessing HDL and its impact on health. While serum HDL-C measurement remains a valuable marker, it should be interpreted not only in the context of other lipid parameters but the rest of the blood chemistry story, as well as other variables such as patient history. Advanced lipoprotein testing, for example, includes measurement of HDL particle number, size distribution, and functional assays like cholesterol efflux.

Rethinking Reference Ranges

The emerging evidence challenging the "higher is better" paradigm for HDL-C necessitates a reevaluation of the current reference ranges used in clinical practice. Traditional guidelines have focused on identifying low HDL-C as a risk factor, with levels below 40 mg/dL for men and 50 mg/dL for women considered suboptimal [4]. However, these cutoffs do not account for the potential risks associated with very high HDL-C levels or the U-shaped relationship between HDL-C and health outcomes observed in recent studies.

Based on the cumulative evidence from large-scale epidemiological studies and the mechanistic insights into HDL function, we propose a more nuanced approach to HDL-C reference ranges:

Proposed Optimal HDL-C Ranges:

Proposed Optimal HDL-C Ranges:

- Men: 55-75 mg/dL (1.4-1.9 mmol/L)

- Women: 65-85 mg/dL (1.7-2.2 mmol/L)

These ranges are well-supported by the evidence presented here. They are backed by multiple large-scale epidemiological studies, particularly the Copenhagen and CANHEART studies and account for the U-shaped morality curve presented in a number of research papers. Based on the current evidence, the above ranges are likely at a level that maintains HDL's optimal physiological functionality, and they are conservative enough to avoid higher ranges where risks have been observed.

It is worth noting that these ranges could be viewed as somewhat narrow, but should be interpreted flexibly based on individual factors like age, ethnicity, and overall health status presented elsewhere in this article.

Rationale for the proposed ranges:

Rationale for the proposed ranges:

- Lower Bound: The lower bounds of these ranges are set above the traditional cutoffs for low HDL-C, reflecting the consistent evidence of increased cardiovascular risk at lower levels. These values are supported by studies showing a plateau in risk reduction above these levels [34].

- Upper Bound: The upper bounds are set based on the evidence of increased all-cause mortality and potential dysfunction of HDL particles at very high concentrations. The CANHEART study and the Copenhagen General Population Study both observed increased risks at levels above these ranges [5,6].

- Gender Differences: The higher range for women reflects the naturally higher HDL-C levels observed in females and is consistent with the gender-specific patterns observed in population studies [35].

- Risk Inflection Points: These ranges encompass the HDL-C levels associated with the lowest mortality risk in large population studies. For example, Madsen et al. found the lowest risk at 1.9 mmol/L (73 mg/dL) for men and 2.4 mmol/L (93 mg/dL) for women [5].

- Functional Considerations: These ranges are likely to represent HDL particles that maintain optimal functionality in terms of cholesterol efflux capacity and anti-inflammatory properties, based on studies of HDL function across different concentration ranges [36].

It's important to note that these proposed ranges should be interpreted in the context of an individual's overall risk profile and should not be viewed as rigid cutoffs. Factors to consider when interpreting HDL-C levels that we are not discussing in this article are:

- Age: The relationship between HDL-C and cardiovascular risk may vary with age, with some studies suggesting a weaker association in older adults [37].

- Race/Ethnicity: There are known racial and ethnic differences in HDL-C levels and their association with cardiovascular risk [38].

- Presence of Other Risk Factors: The impact of HDL-C levels should be considered in the context of other cardiovascular risk factors, including LDL-C, triglycerides, blood pressure, and diabetes status.

- Lifestyle Factors: Diet, physical activity, alcohol consumption, and smoking can all influence HDL-C levels and should be taken into account [39].

- Medications: Certain medications, such as statins, fibrates, and hormone replacement therapy, can affect HDL-C levels [40].

The re-appraisal of the scientific literature and proposed reference ranges represent a step towards a more nuanced understanding of HDL-C's role in health and disease. They aim to identify not only individuals at risk due to low HDL-C but also those who may be at increased risk despite (or because of) very high levels. However, it is important to remember that HDL-C is just one piece of the complex puzzle of lipid metabolism and cardiovascular risk. A comprehensive approach that considers multiple risk factors and emphasizes HDL functionality over mere concentration is likely to provide the most accurate assessment of an individual's cardiovascular health.

Implications for Clinical Practice

The paradigm shift in our understanding of HDL-C and its relationship to health outcomes has significant implications for both clinical practice and future research directions. As we move towards a more nuanced view of HDL, several key areas require attention:

Ways Forward For Clinicians

- Risk Assessment: Current cardiovascular risk assessment tools that incorporate HDL-C as a linear variable should be reevaluated. New algorithms that account for the U-shaped relationship between HDL-C and outcomes need to be developed and validated [41].

- Patient Education: Healthcare providers should educate patients about the complex nature of HDL-C, moving away from the simplistic "good cholesterol" narrative. Patients with very high HDL-C levels should be informed about potential risks and the importance of overall lipid profile and lifestyle factors [40].

- Therapeutic Targets: The focus of lipid management should shift from simply raising HDL-C levels to optimizing overall lipid profile and enhancing HDL functionality. This may involve combination therapies that address multiple lipid parameters simultaneously [39].

- Personalized Medicine: Given the heterogeneity in HDL particles and their effects, a more personalized approach to lipid management is needed. This could involve advanced lipoprotein testing and consideration of genetic factors that influence HDL metabolism [44].

- Monitoring and Follow-up: Regular monitoring of lipid profiles, including HDL-C, remains important. However, interpretation should consider trends over time and changes in relation to other risk factors and lifestyle modifications [45].

- Lifestyle Interventions: While pharmacological raising of HDL-C has shown limited benefit, lifestyle interventions that improve overall metabolic health (e.g., exercise, Mediterranean diet) should be emphasized as they may improve HDL functionality in addition to affecting HDL-C levels [46].

| Study | Participants | Duration | Key Findings | Limitations |

| Liu et al. (2022)[13] | 66 older adults | 4 months | Improved muscle endurance, no significant change in walking distance | Small sample size, short duration |

| Andreux et al. (2019)[14] | 60 elderly individuals | 4 weeks | Improved mitochondrial gene expression in muscle | Short duration, limited functional outcomes |

| Singh et al. (2022)[15] | 88 middle-aged adults | 4 months | Improved muscle strength and exercise performance | Industry-funded, limited long-term data |

"The HDL paradox serves as a valuable lesson in the importance of continual scientific inquiry and the need to challenge established paradigms. It reminds us that biology is often more complex than our models suggest and that our understanding is always a work in progress."

Conclusion

The HDL paradox serves as a valuable lesson in the importance of continual scientific inquiry and the need to challenge established paradigms. It reminds us that biology is often more complex than our models suggest and that our understanding is always a work in progress. As we continue to unravel the intricacies of lipid metabolism, we move closer to more effective strategies for preventing cardiovascular disease and promoting overall health. The journey of HDL from "good cholesterol" to a complex, multifaceted player in human health exemplifies the dynamic nature of medical science and the ongoing quest for a deeper understanding of human biology.

References

- Gordon T, Castelli WP, Hjortland MC, Kannel WB, Dawber TR. High density lipoprotein as a protective factor against coronary heart disease. The Framingham Study. Am J Med. 1977;62(5):707-714. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(77)90874-9

- Assmann G, Schulte H, von Eckardstein A, Huang Y. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol as a predictor of coronary heart disease risk. The PROCAM experience and pathophysiological implications for reverse cholesterol transport. Atherosclerosis. 1996;124 Suppl. doi:10.1016/0021-9150(96)05852-2

- Glomset JA. The plasma lecithins acyltransferase reaction. J Lipid Res. 1968;9(2):155-167.

- Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001;285(19):2486-2497. doi:10.1001/jama.285.19.2486

- Madsen CM, Varbo A, Nordestgaard BG. Extreme high high-density lipoprotein cholesterol is paradoxically associated with high mortality in men and women: two prospective cohort studies. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(32):2478-2486. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx163

- Ko DT, Alter DA, Guo H, et al. High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Cause-Specific Mortality in Individuals Without Previous Cardiovascular Conditions: The CANHEART Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(19):2073-2083. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.038

- Hirata A, Sugiyama D, Watanabe M, et al. Association of extremely high levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol with cardiovascular mortality in a pooled analysis of 9 cohort studies including 43,407 individuals: The EPOCH-JAPAN study. J Clin Lipidol. 2018;12(3):674-684.e5. doi:10.1016/j.jacl.2018.01.014

- Huang Y, DiDonato JA, Levison BS, et al. An abundant dysfunctional apolipoprotein A1 in human atheroma. Nat Med. 2014;20(2):193-203. doi:10.1038/nm.3459

- Ansell BJ, Navab M, Hama S, et al. Inflammatory/antiinflammatory properties of high-density lipoprotein distinguish patients from control subjects better than high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and are favorably affected by simvastatin treatment. Circulation. 2003;108(22):2751-2756. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000103624.14436.4B

- Kontush A, Chapman MJ. Functionally defective high-density lipoprotein: a new therapeutic target at the crossroads of dyslipidemia, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58(3):342-374. doi:10.1124/pr.58.3.1

- Zanoni P, Khetarpal SA, Larach DB, et al. Rare variant in scavenger receptor BI raises HDL cholesterol and increases risk of coronary heart disease. Science. 2016;351(6278):1166-1171. doi:10.1126/science.aad3517

- Shao B, Oda MN, Oram JF, Heinecke JW. Myeloperoxidase: an oxidative pathway for generating dysfunctional high-density lipoprotein. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23(3):447-454. doi:10.1021/tx9003775

- Levels JH, Abraham PR, van den Ende A, van Deventer SJ. Distribution and kinetics of lipoprotein-bound endotoxin. Infect Immun. 2001;69(5):2821-2828. doi:10.1128/IAI.69.5.2821-2828.2001

- Murphy AJ, Woollard KJ, Hoang A, et al. High-density lipoprotein reduces the human monocyte inflammatory response. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(11):2071-2077. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.168690

- Singh IP, Chopra AK, Coppenhaver DH, Ananatharamaiah GM, Baron S. Lipoproteins account for part of the broad non-specific antiviral activity of human serum. Antiviral Res. 1999;42(3):211-218. doi:10.1016/s0166-3542(99)00032-7

- Madsen CM, Varbo A, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Frikke-Schmidt R, Nordestgaard BG. U-shaped relationship of HDL and risk of infectious disease: two prospective population-based cohort studies. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(14):1181-1190. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx665

- Wei X, Zeng W, Su J, et al. Hypolipidemia is associated with the severity of COVID-19. J Clin Lipidol. 2020;14(3):297-304. doi:10.1016/j.jacl.2020.04.008

- Jafri H, Alsheikh-Ali AA, Karas RH. Baseline and on-treatment high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and the risk of cancer in randomized controlled trials of lipid-altering therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(25):2846-2854. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.069

- Jafri H, Alsheikh-Ali AA, Karas RH. Meta-analysis: statin therapy does not alter the association between low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and increased cardiovascular risk. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(12):800-808. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-153-12-201012210-00006

- Button EB, Robert J, Caffrey TM, Fan J, Zhao W, Wellington CL. HDL from an Alzheimer's disease perspective. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2019;30(3):224-234. doi:10.1097/MOL.0000000000000604

- Huang X, Auinger P, Eberly S, et al. Serum cholesterol and the progression of Parkinson's disease: results from DATATOP. PLoS One. 2011;6(8). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022854

- Charles-Schoeman C, Lee YY, Grijalva V, et al. Cholesterol efflux by high density lipoproteins is impaired in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(7):1157-1162. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200493

- McMahon M, Grossman J, FitzGerald J, et al. Proinflammatory high-density lipoprotein as a biomarker for atherosclerosis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(8):2541-2549. doi:10.1002/art.21976

- Zewinger S, Speer T, Kleber ME, et al. HDL cholesterol is not associated with lower mortality in patients with kidney dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(5):1073-1082. doi:10.1681/ASN.2013050482

- Siddiqui MS, Fuchs M, Idowu MO, et al. Severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and progression to cirrhosis are associated with atherogenic lipoprotein profile. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(5):1000-8.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2014.10.008

- Voight BF, Peloso GM, Orho-Melander M, et al. Plasma HDL cholesterol and risk of myocardial infarction: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet. 2012;380(9841):572-580. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60312-2

- Barter PJ, Caulfield M, Eriksson M, et al. Effects of torcetrapib in patients at high risk for coronary events. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(21):2109-2122. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0706628

- Rosenson RS, Brewer HB Jr, Chapman MJ, et al. HDL measures, particle heterogeneity, proposed nomenclature, and relation to atherosclerotic cardiovascular events. Clin Chem. 2011;57(3):392-410. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2010.155333

- Rohatgi A, Khera A, Berry JD, et al. HDL cholesterol efflux capacity and incident cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(25):2383-2393. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1409065

- Moradi H, Vaziri ND, Kashyap ML, Said HM, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Role of HDL dysfunction in end-stage renal disease: a double-edged sword. J Ren Nutr. 2013;23(3):203-206. doi:10.1053/j.jrn.2013.01.022

- Rosenson RS, Brewer HB Jr, Ansell BJ, et al. Dysfunctional HDL and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2016;13(1):48-60. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2015.124

- Camont L, Chapman MJ, Kontush A. Biological activities of HDL subpopulations and their relevance to cardiovascular disease. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17(10):594-603. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2011.05.013

- Johannsen TH, Frikke-Schmidt R, Schou J, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjærg-Hansen A. Genetic inhibition of CETP, ischemic vascular disease and mortality, and possible adverse effects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(20):2041-2048. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.045

- Barter P, Gotto AM, LaRosa JC, et al. HDL cholesterol, very low levels of LDL cholesterol, and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(13):1301-1310. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa064278

- Soran H, Schofield JD, Durrington PN. Antioxidant properties of HDL. Front Pharmacol. 2015;6:222. doi:10.3389/fphar.2015.00222

- Khera AV, Cuchel M, de la Llera-Moya M, et al. Cholesterol efflux capacity, high-density lipoprotein function, and atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(2):127-135. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1001689

- Agarwala AP, Rodrigues A, Risman M, et al. High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL) Phospholipid Content and Cholesterol Efflux Capacity Are Reduced in Patients With Very High HDL Cholesterol and Coronary Disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(6):1515-1519. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305504

- Chandra A, Neeland IJ, Berry JD, et al. The relationship of body mass and fat distribution with incident hypertension: observations from the Dallas Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(10):997-1002. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.05.057

- Rader DJ, Hovingh GK. HDL and cardiovascular disease. Lancet. 2014;384(9943):618-625. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61217-4

- Rosenson RS, Brewer HB Jr, Barter PJ, et al. HDL and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: genetic insights into complex biology. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15(1):9-19. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2017.115

- Mora S, Glynn RJ, Ridker PM. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, size, particle number, and residual vascular risk after potent statin therapy. Circulation. 2013;128(11):1189-1197. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002671

- Rosenson RS, Brewer HB Jr, Barter PJ, et al. HDL and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: genetic insights into complex biology. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15(1):9-19. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2017.115

- Rader DJ, Hovingh GK. HDL and cardiovascular disease. Lancet. 2014;384(9943):618-625. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61217-4

- Rosenson RS, Brewer HB Jr, Ansell B, et al. Translation of high-density lipoprotein function into clinical practice: current prospects and future challenges. Circulation. 2013;128(11):1256-1267. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.000962

- Mora S. Advanced lipoprotein testing and subfractionation are not (yet) ready for routine clinical use. Circulation. 2009;119(17):2396-2404. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.819359

- Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(25). doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1800389

Chris

"This should be 101 level teaching for anyone studying to be a healthcare practitioner. I tremendously appreciate the insights presented here."

Dr Kang

“Extremely helpful. I have been wondering what could be the balancing pivot for especially older adults who should be ingesting slightly higher amounts of protein but yet be able to mitigate age-related bone loss risks. This clinical content session answered the question. Dr. Walsh has done it again, by translating evidence-based insights into practical clinical implementation that we could use immediately.”

Learn this, and so much more in our clinical mentorship, Clinician's Code Foundation Professional Certificate where we help practitioners build confidence, cut overwhelm, and become successful in Functional Medicine.

Sadie

"I LOVE everything about these presentations. It makes me excited to practice. 😊"

Carrie

"This is incredible information Dr Walsh."

Fernando

"Another outstanding presentation...

Thank you!"

Thank you!"

Khaled

"You ground me from all the FM Hype out there, which is mostly messy, biased, and FOMO driven. Please keep doing what you're doing. Your work is benefiting so many patients around the globe. Truly blessed to be amongst your students. Much love ❤️"

Get Free Functional Medicine Education

Thank you!

Policy Pages

Join our mailing list

Get updates and special offers right in your mailbox.

Thank you!

Learn the PRAL Score of 30 Common Foods

(Based on Portion Sizes)

And get started evaluating your diet today!

Enter your email address below to subscribe to our mailing list and get the guide free!

Thank you!

Grab our free Reactive Hypoglycemia Playbook

Enter your email address below to subscribe to our mailing list and get the guide free!

Thank you!

See Inside the Program

Fill in your information below and we'll give you access to a free inside look into the entire program.

Thank you!

Get Free Stuff!

Fill in your information below and we'll give you our 100+ page eBook "Overloaded", our one hour "State of the Industry" webinar, and a sneak peek into one of our courses.