Akkermansia: Probiotic Panacea or Overhyped Organism?

Nov 4

/

Drs. Bryan & Julie Walsh

Introduction

Akkermansia muciniphila has been hailed as a potential probiotic panacea, with promising research suggesting it may offer benefits for gut health, metabolic regulation, and immune function. As this gut bacterium gains increasing attention, it is crucial to take a critical look at the current state of the evidence and examine both the promise and limitations of this emerging probiotic candidate.

This article provides an analysis of Akkermansia muciniphila, exploring its proposed mechanisms of action, the findings from human clinical trials, and the key concerns and shortcomings that must be addressed. By taking a balanced and evidence-based approach, we aim to separate hype from reality, guiding practitioners towards a nuanced understanding of this interesting but unproven microorganism and its potential therapeutic applications.

The tendency to quickly embrace new and exciting supplements as potential cures-all is a persistent issue in the functional medicine and nutrition industry. Time and again, supplements have been promoted as miraculous solutions, only to later face scrutiny as the hype outpaced the scientific evidence. Examples include resveratrol, green coffee bean extract, and raspberry ketones, to name a few, all of which were touted as weight loss and metabolic wonder-compounds before rigorous research ultimately failed to support the initial claims. With Akkermansia muciniphila now gaining significant attention, it is crucial to approach this potential probiotic with a critical eye, carefully weighing the current data and limitations before making any definitive conclusions about its efficacy and safety.

Proposed Mechanisms of Action

Gut Barrier Function

Akkermansia muciniphila has garnered significant attention in the scientific community due to its potential role in enhancing intestinal barrier integrity. This gram-negative anaerobe, which resides in the mucus layer of the human gastrointestinal tract, is thought to play a crucial role in maintaining gut health through several mechanisms.

One of the primary proposed mechanisms of action for Akkermansia muciniphila is its ability to increase mucus thickness and enhance the expression of tight junction proteins. These effects are believed to contribute to the prevention of "leaky gut" syndrome and associated inflammatory conditions [1]. The mucus layer serves as a critical barrier between the gut lumen and the epithelial cells, protecting against potential pathogens and maintaining a healthy gut environment.

Research has shown that Akkermansia muciniphila can stimulate the production of mucin by goblet cells, thereby increasing the thickness of the protective mucus layer [2]. This thicker mucus layer may provide enhanced protection against harmful bacteria and toxins, potentially reducing the risk of intestinal inflammation and associated disorders.

Furthermore, Akkermansia muciniphila has been observed to influence the expression of tight junction proteins, such as occludin and claudin, which are essential for maintaining the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier [3]. By strengthening these tight junctions, Akkermansia muciniphila may help prevent the translocation of harmful substances from the gut lumen into the bloodstream, a process implicated in various inflammatory and metabolic disorders.

However, it is important to note that while these mechanisms have been demonstrated in preclinical (aka animal) studies, their translation to human health outcomes remains to be fully elucidated. The complex interactions between Akkermansia muciniphila, the host, and other members of the gut microbiome warrant further investigation to fully understand the extent of its impact on gut barrier function.

One of the primary proposed mechanisms of action for Akkermansia muciniphila is its ability to increase mucus thickness and enhance the expression of tight junction proteins. These effects are believed to contribute to the prevention of "leaky gut" syndrome and associated inflammatory conditions [1]. The mucus layer serves as a critical barrier between the gut lumen and the epithelial cells, protecting against potential pathogens and maintaining a healthy gut environment.

Research has shown that Akkermansia muciniphila can stimulate the production of mucin by goblet cells, thereby increasing the thickness of the protective mucus layer [2]. This thicker mucus layer may provide enhanced protection against harmful bacteria and toxins, potentially reducing the risk of intestinal inflammation and associated disorders.

Furthermore, Akkermansia muciniphila has been observed to influence the expression of tight junction proteins, such as occludin and claudin, which are essential for maintaining the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier [3]. By strengthening these tight junctions, Akkermansia muciniphila may help prevent the translocation of harmful substances from the gut lumen into the bloodstream, a process implicated in various inflammatory and metabolic disorders.

However, it is important to note that while these mechanisms have been demonstrated in preclinical (aka animal) studies, their translation to human health outcomes remains to be fully elucidated. The complex interactions between Akkermansia muciniphila, the host, and other members of the gut microbiome warrant further investigation to fully understand the extent of its impact on gut barrier function.

Metabolic Regulation

Another area of significant interest regarding Akkermansia muciniphila is its potential role in metabolic regulation, particularly in the context of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Several studies have suggested that this bacterium may have beneficial effects on glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity [4].

One proposed mechanism by which Akkermansia muciniphila may influence metabolic health is through the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), particularly propionate and acetate [5]. These SCFAs have been shown to play important roles in energy homeostasis, glucose metabolism, and appetite regulation. By increasing the production of these beneficial metabolites, Akkermansia muciniphila may contribute to improved metabolic health.

Additionally, research has indicated that Akkermansia muciniphila may influence the expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism and glucose homeostasis [6]. For instance, studies in animal models have shown that supplementation with Akkermansia muciniphila can lead to increased expression of Fiaf (fasting-induced adipose factor), a protein that inhibits lipoprotein lipase and may protect against diet-induced obesity [7].

Moreover, Akkermansia muciniphila has been associated with improvements in insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance in preclinical studies [8]. These effects may be mediated, in part, by the bacterium's ability to modulate the endocannabinoid system, which plays a role in energy homeostasis and metabolism [9].

While these findings are promising, it is crucial to emphasize that most of the evidence supporting Akkermansia muciniphila's role in metabolic regulation comes from animal studies. The translation of these effects to human physiology and their clinical relevance remain areas of active research and debate.

"While many studies have reported beneficial effects on overall microbiome composition, the complex ecological interactions within the gut ecosystem make it challenging to predict the long-term effects of artificially elevating Akkermansia muciniphila levels."

Immune Modulation

The potential immunomodulatory effects of Akkermansia muciniphila represent another intriguing aspect of its proposed mechanisms of action. This bacterium is thought to influence immune responses through direct interactions with intestinal immune cells and by modulating inflammatory processes [10].

Research has shown that Akkermansia muciniphila can interact with Toll-like receptors (TLRs) on intestinal epithelial cells and immune cells, potentially influencing the production of cytokines and other immune mediators [11]. For instance, studies have demonstrated that Akkermansia muciniphila can stimulate the production of interleukin-10 (IL-10), an anti-inflammatory cytokine, while reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) [12].

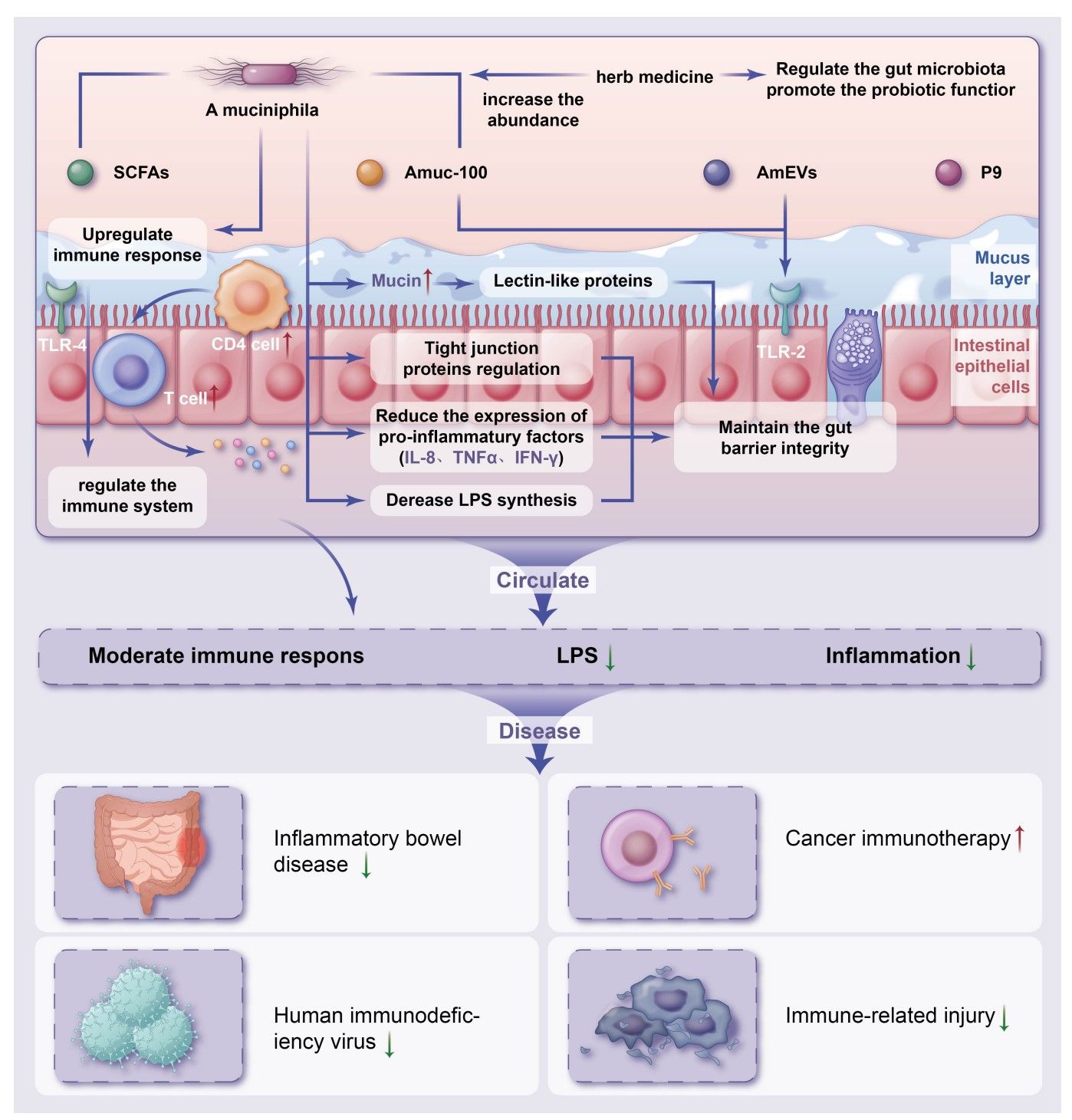

Furthermore, Akkermansia muciniphila has been associated with increased numbers of regulatory T cells (Tregs) in the intestinal mucosa [13]. Tregs play a crucial role in maintaining immune tolerance and preventing excessive inflammatory responses. By promoting Treg development and function, Akkermansia muciniphila may contribute to a more balanced immune environment in the gut. (Figure 1)

It is important to note, however, that the immune-modulating effects of Akkermansia muciniphila may be context-dependent. While many studies have reported anti-inflammatory effects, some research has suggested that in certain conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), increased abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila may be associated with pro-inflammatory responses [15]. This highlights the complex nature of host-microbe interactions and the need for further research to fully understand the immunomodulatory potential of Akkermansia muciniphila in different health contexts.

Research has shown that Akkermansia muciniphila can interact with Toll-like receptors (TLRs) on intestinal epithelial cells and immune cells, potentially influencing the production of cytokines and other immune mediators [11]. For instance, studies have demonstrated that Akkermansia muciniphila can stimulate the production of interleukin-10 (IL-10), an anti-inflammatory cytokine, while reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) [12].

Furthermore, Akkermansia muciniphila has been associated with increased numbers of regulatory T cells (Tregs) in the intestinal mucosa [13]. Tregs play a crucial role in maintaining immune tolerance and preventing excessive inflammatory responses. By promoting Treg development and function, Akkermansia muciniphila may contribute to a more balanced immune environment in the gut. (Figure 1)

Another proposed mechanism by which Akkermansia muciniphila may modulate immune function is through its effects on the intestinal barrier. By enhancing barrier integrity, as discussed earlier, Akkermansia muciniphila may help prevent the translocation of bacterial antigens and reduce systemic inflammation [14].

It is important to note, however, that the immune-modulating effects of Akkermansia muciniphila may be context-dependent. While many studies have reported anti-inflammatory effects, some research has suggested that in certain conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), increased abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila may be associated with pro-inflammatory responses [15]. This highlights the complex nature of host-microbe interactions and the need for further research to fully understand the immunomodulatory potential of Akkermansia muciniphila in different health contexts.

Figure 1

(From Ding X, Meng PF, Ma XX, Yue JY, Li LP, Xu LR. Akkermansia muciniphila and herbal medicine in immune-related diseases: current evidence and future perspectives. Front Microbiomes. 2024;3:1276015. doi:10.3389/frmbi.2024.1276015)

Evidence from Human Clinical Trials

While the proposed mechanisms of action for Akkermansia muciniphila are intriguing, it is crucial to examine the available evidence from human clinical trials to assess its potential as a probiotic. To date, human clinical data on Akkermansia muciniphila remains limited, with most evidence coming from animal studies and observational human studies.

One of the most notable human clinical trials involving Akkermansia muciniphila was a small proof-of-concept study conducted by Depommier et al. in 2019 [16]. This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study involved 32 overweight or obese insulin-resistant volunteers who were supplemented with either live or pasteurized Akkermansia muciniphila (1010 CFU/day) or a placebo for three months.

The results of this study showed that supplementation with pasteurized Akkermansia muciniphila led to improvements in several metabolic parameters:

- Insulin sensitivity (as measured by the Matsuda index) improved by 28.62 ± 7.02% (p = 0.002) in the pasteurized Akkermansia muciniphila group compared to placebo.

- Total plasma cholesterol levels decreased by 8.68 ± 2.45% (p = 0.02) in the pasteurized Akkermansia muciniphila group.

- Body weight (-2.27 ± 0.92 kg, p = 0.091) and fat mass (-1.37 ± 0.82 kg, p = 0.092) showed trends towards reduction in the pasteurized Akkermansia muciniphila group, although these did not reach statistical significance.

Interestingly, the live Akkermansia muciniphila group did not show significant improvements in these parameters, suggesting that the pasteurization process may enhance the beneficial effects of the bacterium.

While these results are promising, it is important to note several limitations of this study:

- The sample size was small (n=32), limiting the generalizability of the findings.

- The study duration was relatively short (3 months), and long-term effects were not assessed.

- The study focused on a specific population (overweight/obese insulin-resistant adults), and the effects in other populations remain unknown.

Despite these encouraging findings, the overall body of human clinical evidence for Akkermansia muciniphila remains limited. Most studies have been small in scale and of short duration, focusing primarily on metabolic outcomes in specific populations. Larger, longer-term clinical trials are needed to confirm these initial findings and to explore the potential benefits and risks of Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation in diverse populations and health conditions.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that most human studies have focused on a single strain of Akkermansia muciniphila (ATCC BAA-835), and the effects of other strains or preparations (e.g., live vs. pasteurized) remain largely unexplored in human trials.

In summary, while the available human clinical data on Akkermansia muciniphila is promising, it is still limited in scope and scale. More robust, large-scale clinical trials are needed to establish the efficacy, optimal dosing, and long-term safety of Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation in humans.

Shortcomings and Concerns

Limited Human Data

One of the primary shortcomings in the current state of Akkermansia muciniphila research is the limited availability of human clinical data. While numerous animal studies have demonstrated promising effects, the translation of these findings to human physiology and clinical outcomes remains uncertain.

The majority of evidence supporting the potential benefits of Akkermansia muciniphila comes from preclinical studies in animal models, particularly mice. While these studies have provided valuable insights into potential mechanisms of action, it is well-established that findings in animal models do not always translate directly to human outcomes. The complex interactions between the gut microbiome, host physiology, and environmental factors in humans may lead to different responses to Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation compared to those observed in controlled animal studies.

Furthermore, the few human studies that have been conducted are generally small in scale and of short duration. For example, the aforementioned study by Depommier et al. [16] included only 32 participants and lasted for three months. While this study provided important proof-of-concept data, larger and longer-term studies are needed to confirm these findings and assess the long-term effects and safety of Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation.

The limited human data also means that we have insufficient information about potential variability in response to Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation across different populations. Factors such as age, sex, ethnicity, baseline health status, and existing gut microbiome composition may all influence an individual's response to probiotic supplementation, and these variables have not been adequately explored in the context of Akkermansia muciniphila.

Strain Specificity

Another important consideration in the evaluation of Akkermansia muciniphila as a probiotic is the issue of strain specificity. Most studies to date have focused on a single strain of Akkermansia muciniphila, namely ATCC BAA-835, which was originally isolated from a healthy human fecal sample [17].

However, recent research has revealed that there is significant genomic diversity among Akkermansia muciniphila strains [18]. Different strains may possess varying functional capabilities and potentially different effects on host physiology. This strain-level variation could have important implications for the development of Akkermansia muciniphila as a probiotic, as the effects observed with one strain may not necessarily be generalizable to others.

Moreover, the focus on a single strain in most studies limits our understanding of the potential diversity of Akkermansia muciniphila's effects. It is possible that different strains could have distinct or even opposing effects on host health, depending on their specific genetic makeup and functional capabilities.

The issue of strain specificity also raises questions about the optimal preparation of Akkermansia muciniphila for probiotic use. For instance, the study by Depommier et al. [16] found that pasteurized Akkermansia muciniphila had more pronounced beneficial effects than live bacteria. This suggests that the active components responsible for the observed effects may be heat-stable and potentially strain-specific.

However, recent research has revealed that there is significant genomic diversity among Akkermansia muciniphila strains [18]. Different strains may possess varying functional capabilities and potentially different effects on host physiology. This strain-level variation could have important implications for the development of Akkermansia muciniphila as a probiotic, as the effects observed with one strain may not necessarily be generalizable to others.

Moreover, the focus on a single strain in most studies limits our understanding of the potential diversity of Akkermansia muciniphila's effects. It is possible that different strains could have distinct or even opposing effects on host health, depending on their specific genetic makeup and functional capabilities.

The issue of strain specificity also raises questions about the optimal preparation of Akkermansia muciniphila for probiotic use. For instance, the study by Depommier et al. [16] found that pasteurized Akkermansia muciniphila had more pronounced beneficial effects than live bacteria. This suggests that the active components responsible for the observed effects may be heat-stable and potentially strain-specific.

Potential Adverse Effects

While many studies have reported beneficial effects of Akkermansia muciniphila, it is crucial to consider potential adverse effects, particularly in certain contexts or populations. One area of concern is the potential role of Akkermansia muciniphila in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Some studies have reported increased abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila in patients with IBD, particularly ulcerative colitis [19]. While the causal relationship between Akkermansia muciniphila abundance and IBD severity remains unclear, these findings raise questions about the safety of Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation in individuals with or at risk for IBD.

Furthermore, as Akkermansia muciniphila is a mucin-degrading bacterium, there are theoretical concerns about its potential to compromise the mucus layer in certain conditions. While studies have generally shown that Akkermansia muciniphila enhances rather than degrades the mucus layer, the effects in individuals with pre-existing gut barrier dysfunction or in the context of certain diseases remain to be fully elucidated.

Another potential concern is the interaction of Akkermansia muciniphila with other members of the gut microbiome. While many studies have reported beneficial effects on overall microbiome composition, the complex ecological interactions within the gut ecosystem make it challenging to predict the long-term effects of artificially elevating Akkermansia muciniphila levels.

Some studies have reported increased abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila in patients with IBD, particularly ulcerative colitis [19]. While the causal relationship between Akkermansia muciniphila abundance and IBD severity remains unclear, these findings raise questions about the safety of Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation in individuals with or at risk for IBD.

Furthermore, as Akkermansia muciniphila is a mucin-degrading bacterium, there are theoretical concerns about its potential to compromise the mucus layer in certain conditions. While studies have generally shown that Akkermansia muciniphila enhances rather than degrades the mucus layer, the effects in individuals with pre-existing gut barrier dysfunction or in the context of certain diseases remain to be fully elucidated.

Another potential concern is the interaction of Akkermansia muciniphila with other members of the gut microbiome. While many studies have reported beneficial effects on overall microbiome composition, the complex ecological interactions within the gut ecosystem make it challenging to predict the long-term effects of artificially elevating Akkermansia muciniphila levels.

Dosage and Administration

The optimal dosage, duration of use, and delivery methods for Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation remain unclear. Clinical trials have used doses ranging from 109 to 1010 CFU daily, but the dose-response relationship and the effects of long-term supplementation at these doses have not been thoroughly investigated.

Moreover, the most effective form of Akkermansia muciniphila for supplementation (live, pasteurized, or specific components) remains to be determined. The finding that pasteurized Akkermansia muciniphila may be more effective than live bacteria in some contexts [16] raises questions about the optimal preparation and delivery methods for this potential probiotic.

Moreover, the most effective form of Akkermansia muciniphila for supplementation (live, pasteurized, or specific components) remains to be determined. The finding that pasteurized Akkermansia muciniphila may be more effective than live bacteria in some contexts [16] raises questions about the optimal preparation and delivery methods for this potential probiotic.

Long-term Safety

Perhaps one of the most significant concerns regarding Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation is the lack of data on long-term safety. Most studies to date have been of relatively short duration (typically 3 months or less), and the long-term effects of artificially elevating Akkermansia muciniphila levels in the gut are unknown.

Given the complex and dynamic nature of the gut microbiome, it is crucial to understand the potential long-term ecological effects of sustained Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation. Questions remain about whether long-term use could lead to dysbiosis, alter the balance of other beneficial bacteria, or potentially have unforeseen effects on host physiology.

Furthermore, the safety profile in different populations, such as the elderly, pregnant women, or individuals with compromised immune function, has not been adequately studied. These populations may be more vulnerable to potential adverse effects and require careful consideration before Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation can be recommended.

Given the complex and dynamic nature of the gut microbiome, it is crucial to understand the potential long-term ecological effects of sustained Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation. Questions remain about whether long-term use could lead to dysbiosis, alter the balance of other beneficial bacteria, or potentially have unforeseen effects on host physiology.

Furthermore, the safety profile in different populations, such as the elderly, pregnant women, or individuals with compromised immune function, has not been adequately studied. These populations may be more vulnerable to potential adverse effects and require careful consideration before Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation can be recommended.

Considerations for Use

Given the promising yet preliminary nature of the evidence surrounding A. muciniphila, careful consideration is needed when contemplating its use as a probiotic supplement. Here, we discuss potential candidates for Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation, dosage considerations, duration of use, and potential contraindications.

Potential Candidates

Based on the current evidence, individuals with metabolic disorders, such as obesity or type 2 diabetes, may be the most likely to benefit from Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation. The study by Depommier et al. [16] demonstrated improvements in insulin sensitivity and cholesterol levels in overweight and obese individuals with insulin resistance.

However, it is important to note that these findings are based on limited clinical data, and the effectiveness of Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation in treating or preventing metabolic disorders remains to be conclusively demonstrated. Potential candidates for Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, considering individual health status, risk factors, and potential contraindications.

Dosage

Clinical trials have used doses ranging from 109 to 1010 CFU daily of Akkermansia muciniphila. The study by Depommier et al. [16] used a dose of 1010 CFU/day, which was found to be well-tolerated and associated with metabolic improvements. However, the optimal dosage remains unclear, and dose-response relationships have not been thoroughly investigated.

It is worth noting that the effective dose may vary depending on the form of Akkermansia muciniphila used (live vs. pasteurized) and potentially on individual factors such as baseline gut microbiome composition and metabolic status. Future studies are needed to establish optimal dosing regimens for different populations and health conditions.

Duration

Most studies investigating Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation have administered the probiotic for 3 months or less. The long-term effects of prolonged use are unknown, and there is currently insufficient data to recommend a specific duration of use.

Given the lack of long-term safety data, it would be prudent to approach extended use of Akkermansia muciniphila supplements with caution. If considering long-term use, regular monitoring and reassessment of the need for continued supplementation would be advisable.

"Given these limitations, it is premature to recommend widespread use of Akkermansia muciniphila as a probiotic supplement. Despite its potential for treating metabolic disorders like obesity and type 2 diabetes, Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation lacks robust human trials compared to proven interventions such as fiber intake and calorie restriction."

Contraindications

While A. muciniphila has shown promise in certain contexts, there are several potential contraindications to consider:

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Given the conflicting data on Akkermansia muciniphila abundance in IBD and the potential for exacerbation of inflammation, caution is advised for individuals with IBD until more safety data is available.

- Compromised Immune Function: The safety of Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation in immunocompromised individuals has not been adequately studied. These individuals may be at higher risk for potential adverse effects and should consult with a healthcare provider before considering Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation.

- Pregnancy and Lactation: The safety of Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation during pregnancy and lactation has not been established. Given the lack of data, it would be prudent to avoid supplementation in these populations until further research is conducted.

- Children: Most studies on Akkermansia muciniphila have been conducted in adult populations. The safety and efficacy in pediatric populations remain unknown, and supplementation in children should be approached with caution.

- Individuals with Severe Gut Barrier Dysfunction: While Akkermansia muciniphila has been associated with improved gut barrier function in some studies, individuals with severe pre-existing gut barrier dysfunction should consult with a healthcare provider before considering supplementation.

It is crucial to emphasize that these considerations are based on the current state of knowledge, which is limited. As more research is conducted, our understanding of the appropriate use, dosing, and potential contraindications for Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation may evolve.

Conclusion

Akkermansia muciniphila has emerged as a promising candidate in the field of probiotics, with potential implications for metabolic health, gut barrier function, and immune modulation. The proposed mechanisms of action, including enhancement of gut barrier integrity, improvement of glucose metabolism, and modulation of immune responses, offer intriguing possibilities for therapeutic applications.

However, the current state of evidence surrounding Akkermansia muciniphila is characterized by significant limitations and uncertainties. While preclinical studies have shown promising results, human clinical data remains scarce and limited in scope. The few human trials conducted to date, while encouraging, have been small in scale and of short duration, leaving many questions unanswered about the long-term efficacy and safety of Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation.

Key challenges and areas of uncertainty include:

- Limited human clinical data, with most evidence derived from animal studies.

- Strain specificity and the potential for varying effects among different Akkermansia muciniphila strains.

- Unclear optimal dosage, duration of use, and delivery methods.

- Potential adverse effects, particularly in the context of inflammatory bowel disease and other gut disorders.

- Unknown long-term safety profile and ecological effects on the gut microbiome.

Given these limitations, it is premature to recommend widespread use of Akkermansia muciniphila as a probiotic supplement. Despite its potential for treating metabolic disorders like obesity and type 2 diabetes, Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation lacks robust human trials compared to proven interventions such as fiber intake and calorie restriction.

While Akkermansia muciniphila shows promise as a novel probiotic, the current evidence does not yet support its widespread use. It should be viewed as an interesting but unproven therapeutic option, requiring further rigorous investigation before it can be confidently recommended for clinical application. As research in this field progresses, our understanding of Akkermansia muciniphila's potential benefits, optimal use cases, and safety profile will undoubtedly evolve, potentially opening new avenues for microbiome-based therapies in the future.

References

- Everard A, Belzer C, Geurts L, et al. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(22):9066-9071.

- Ottman N, Geerlings SY, Aalvink S, de Vos WM, Belzer C. Action and function of Akkermansia muciniphila in microbiome ecology, health and disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;31(6):637-642.

- Chelakkot C, Choi Y, Kim DK, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila-derived extracellular vesicles influence gut permeability through the regulation of tight junctions. Exp Mol Med. 2018;50(2).

- Dao MC, Everard A, Aron-Wisnewsky J, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila and improved metabolic health during a dietary intervention in obesity: relationship with gut microbiome richness and ecology. Gut. 2016;65(3):426-436.

- Derrien M, Belzer C, de Vos WM. Akkermansia muciniphila and its role in regulating host functions. Microb Pathog. 2017;106:171-181.

- Plovier H, Everard A, Druart C, et al. A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila or the pasteurized bacterium improves metabolism in obese and diabetic mice. Nat Med. 2017;23(1):107-113.

- Bäckhed F, Ding H, Wang T, et al. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(44):15718-15723.

- Shin NR, Lee JC, Lee HY, et al. An increase in the Akkermansia spp. population induced by metformin treatment improves glucose homeostasis in diet-induced obese mice. Gut. 2014;63(5):727-735.

- Cani PD, de Vos WM. Next-Generation Beneficial Microbes: The Case of Akkermansia muciniphila. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1765.

- Ottman N, Reunanen J, Meijerink M, et al. Pili-like proteins of Akkermansia muciniphila modulate host immune responses and gut barrier function. PLoS One. 2017;12(3).

- Reunanen J, Kainulainen V, Huuskonen L, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila Adheres to Enterocytes and Strengthens the Integrity of the Epithelial Cell Layer. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81(11):3655-3662.

- Ansaldo E, Slayden LC, Ching KL, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila induces intestinal adaptive immune responses during homeostasis. Science. 2019;364(6446):1179-1184.

- Derrien M, Vaughan EE, Plugge CM, de Vos WM. Akkermansia muciniphila gen. nov., sp. nov., a human intestinal mucin-degrading bacterium. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54(Pt 5):1469-1476.

- Png CW, Lindén SK, Gilshenan KS, et al. Mucolytic bacteria with increased prevalence in IBD mucosa augment in vitro utilization of mucin by other bacteria. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(11):2420-2428.

- Ganesh BP, Klopfleisch R, Loh G, Blaut M. Commensal Akkermansia muciniphila exacerbates gut inflammation in Salmonella Typhimurium-infected gnotobiotic mice. PLoS One. 2013;8(9).

- Depommier C, Everard A, Druart C, et al. Supplementation with Akkermansia muciniphila in overweight and obese human volunteers: a proof-of-concept exploratory study. Nat Med. 2019;25(7):1096-1103.

- Derrien M, Vaughan EE, Plugge CM, de Vos WM. Akkermansia muciniphila gen. nov., sp. nov., a human intestinal mucin-degrading bacterium. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54(Pt 5):1469-1476.

- Guo X, Li S, Zhang J, et al. Genome sequencing of 39 Akkermansia muciniphila isolates reveals its population structure, genomic and functional diversity, and global distribution in mammalian gut microbiotas. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1):800.

- Png CW, Lindén SK, Gilshenan KS, et al. Mucolytic bacteria with increased prevalence in IBD mucosa augment in vitro utilization of mucin by other bacteria. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(11):2420-2428.

Chris

"This should be 101 level teaching for anyone studying to be a healthcare practitioner. I tremendously appreciate the insights presented here."

Dr Kang

“Extremely helpful. I have been wondering what could be the balancing pivot for especially older adults who should be ingesting slightly higher amounts of protein but yet be able to mitigate age-related bone loss risks. This clinical content session answered the question. Dr. Walsh has done it again, by translating evidence-based insights into practical clinical implementation that we could use immediately.”

Learn this, and so much more in our clinical mentorship, Clinician's Code Foundation Professional Certificate where we help practitioners build confidence, cut overwhelm, and become successful in Functional Medicine.

Sadie

"I LOVE everything about these presentations. It makes me excited to practice. 😊"

Carrie

"This is incredible information Dr Walsh."

Fernando

"Another outstanding presentation...

Thank you!"

Thank you!"

Khaled

"You ground me from all the FM Hype out there, which is mostly messy, biased, and FOMO driven. Please keep doing what you're doing. Your work is benefiting so many patients around the globe. Truly blessed to be amongst your students. Much love ❤️"

Get Free Functional Medicine Education

Thank you!

Policy Pages

Join our mailing list

Get updates and special offers right in your mailbox.

Thank you!

Learn the PRAL Score of 30 Common Foods

(Based on Portion Sizes)

And get started evaluating your diet today!

Enter your email address below to subscribe to our mailing list and get the guide free!

Thank you!

Grab our free Reactive Hypoglycemia Playbook

Enter your email address below to subscribe to our mailing list and get the guide free!

Thank you!

See Inside the Program

Fill in your information below and we'll give you access to a free inside look into the entire program.

Thank you!

Get Free Stuff!

Fill in your information below and we'll give you our 100+ page eBook "Overloaded", our one hour "State of the Industry" webinar, and a sneak peek into one of our courses.